Authors: Zaneta Sedilekova (blog post), Jenni Ramos (Jargon Buster)

Date: 23 January 2023

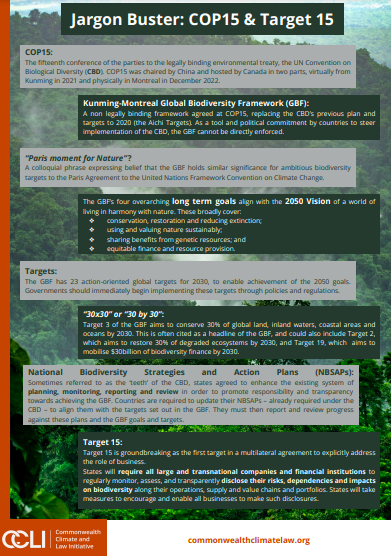

The 15th Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, known as COP15, took place in December 2022 in Montreal, Canada. It resulted in a long-anticipated Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), heralded as a Paris-style agreement for nature. The GBF is groundbreaking in being the first multilateral agreement to set out explicit targets for business. Here we analyse the GBF from a corporate perspective – what impacts may GBF have on companies and financial institutions? How may the global economy change and what should they be preparing for?

GBF Targets with particular relevance to corporates

The GBF contains four overarching long-term global goals and 23 specific targets. The overall framework is designed to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030 and enable people to live in harmony with nature by 2050. All individual targets aim to achieve these broader goals. Not all the targets in GBF are relevant to corporations, with the following targets most likely to have implications for both market, regulatory, legal frameworks governing companies.

- Target 3, also called ‘30×30’ target, which embodies an ambition to conserve 30% of the world’s land, inland waters, coastal areas and ocean by 2030. This ambition will result in the expansion of protected areas from the current roughly 17% of land and 8% of ocean protected worldwide, adding protection to a further 13% of land and 22% of ocean in the next seven years. This may have significant implications for sectors which rely on extraction of living or non-living elements from nature, most significantly agriculture, logging, fisheries and mining. Businesses with supply chain dependencies on these sectors, such as cosmetics, fashion and electronics, may also be impacted in a similar manner. At the same time, businesses operating in tourism and entertainment sectors may benefit from expansion of protected areas.

- Target 7 aims to reduce pollution, including through reducing use of pesticides, hazardous chemicals and working towards eliminating plastic pollution. This may result in national policies and regulations that affect company activities, and could be reinforced by the future agreement of a UN Treaty on plastic pollution.

- Target 14 calls on states to ensure the full integration of biodiversity into policies and regulations across all levels of the government and sectors, and progressively align all public and private activities, fiscal and financial flows with the GBF. This is significant for companies as it is the means by which other targets may be implemented into national laws and regulations.

- Target 15, which asks states to take legal, administrative, or policy measures to encourage and enable business, and in particular to ensure that large and transnational companies and financial institutions, “regularly monitor, assess, and transparently disclose” their biodiversity risks, dependencies, and impacts. These can be impacts manifested through corporate operations, portfolios, supply, and value chains. This specifically includes countries making this disclosure a requirement for all large and transnational companies and financial institutions. The specified aim of Target 15 is to reduce negative impacts on biodiversity, increase positive impacts, reduce biodiversity-related risks to business and financial institutions, and promote sustainable patterns of production.

Target 15 is likely to have profound implications for transnational companies and financial institutions. Monitoring and assessment of biodiversity risks, dependencies and impacts inevitably leads to an increased awareness among corporate management. Such awareness may impact what law perceives as a reasonable level of knowledge to expect from a prudent director when they make decisions on behalf of companies. It is not inconceivable that a failure to take material biodiversity risks, dependencies and impacts into account in corporate decision-making may result in directors facing personal liability for any loss incurred by the company as a result of their decisions. In addition, public disclosure of biodiversity risks, dependencies and impacts is likely to increase biodiversity liability risk, which may result in securities actions or consumer lawsuits against companies and/ or their directors. Finally, even if Target 15 gains recognition only as a voluntary market standard, widespread adoption of such standard may nevertheless change interpretation of relevant laws and have the same effect as outright legislative change (for more information about increasing materiality of biodiversity risk in the corporate sphere, see our recent report Biodiversity Risk: Legal Implications for Companies and their Directors).

- Target 18, which envisages elimination or reform of incentives, such as subsidies that are “harmful to biodiversity” by 2050. This should be achieved by progressively reducing these incentives by at least $500 billion per year by 2030 and by scaling up positive incentives for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use.Target 18 may cause a significant shift of cash from those industries with negative biodiversity impacts that rely heavily on subsidies, most significantly agriculture, fisheries, transport and energy. Related opportunities are likely to open the door for innovation in these industries with both established and news market players competing to attract the redirected finances.

- Target 19, which calls for substantial increase in financial resources and mobilisation of $200bn per year by 2030 from all sources, including private finance. We expect to see a fast and gradual increase in financial resources dedicated to biodiversity protection, conservation and restoration. The private sector may play a crucial role in this by providing financial support and investments via traditional approaches, such as leveraged or blended finance, or innovative (and sometimes controversial) schemes, which may include payment for ecosystem services, biodiversity offsets and credits, benefits-sharing mechanisms and the like. Corporate actors may come under increasing pressure from their investors to proof-test which of these innovative approaches are most effective. At the same time, healthy market competition to identify the most effective solutions means that newcomers may enjoy substantial initial investments in the next five years.

- Indigenous and local communities’ rights are mentioned in the overarching considerations for the GBF in section C and in targets 1, 3, 5, 9, 13, 20 and 22. This includes recognition of land rights when implementing spatial planning and conservation targets, recognising customary use of wild species, equitable benefit sharing and equitable inclusion and representation within decision making. It may result in national policies and regulations that affect company operations and changes to global best practice and corporate governance requirements.

Legal effect of the GBF

Although not a legally binding international treaty, the GBF is designed to affect national laws, policies, regulations, and plans through national implementation measures as governments around the world seek to give effect to their commitments. Observers have noted that the targets in GBF are accompanied by an “enhanced implementation mechanism”, which is modelled on the implementation framework under the 2015 Paris Agreement. System of reporting and monitoring is set to ensure accountability, while the system of gradual ratcheting up of ambitions is designed to enhance progress over time. Against this background coupled with the proven effectiveness of the same mechanism under the 2015 Paris Agreement, the impacts of the above goals under the GBF could be profound.

GBF – a watershed moment for corporate action on biodiversity?

Overall, the GBF has a huge potential to increase awareness of biodiversity risks, impacts and dependencies among corporate actors. Companies need to understand that biodiversity risk is not just another fashionable buzzword but a facet of existing risk categories and a hugely relevant factor in the long term viability and success of many companies. Given that biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse has been ranked within the first four most severe risks in the 10-year horizon in the 2023 Global Risk Report published by the World Economic Forum in January 2023, it is very likely that such increased awareness will translate not only into private sector action in financial and economic terms, but also into increased liability for when things go wrong. For companies and financial institutions alike, a prudent approach may as well entail building an internal capacity to understand their interface with biodiversity and preparing for biodiversity-related disclosures in the world that is set to start its transition to a nature-positive economy in the next decade.

Even in the absence of any hard legal obligations arising from the GBF, the risks and opportunities arising from biodiversity loss are very likely to trigger legal obligations for companies and their directors under existing national company laws and corporate governance frameworks (see Biodiversity Risk: Legal Implications for Companies and their Directors). Directors’ duties to act with loyalty and care, requiring oversight of foreseeable and material risks and opportunities, are interpreted with reference to rapidly evolving market, social and regulatory context. The targets agreed in the GBF further accelerate and underscore this.