Corporate culture – the manifestation of what people do and why they do it – consistently and continuously reflects itself in financial performance. – Tina Mavraki

In this Insight, CCLI climate lawyer Sarah Hill-Smith speaks to Konstantina (Tina) Mavraki, UK Institute of Directors Chartered Portfolio Director, strategic advisor to prominent banks and companies, and author of the Centre for Climate Engagement’s recent Leadership Insight: Corporate Culture (the Report).

Sarah queries Tina about the financial materiality of corporate culture, practical steps directors can take to better understand and manage culture-related risks and opportunities, how to build the internal business case for corporate culture reform and cashflow generation, and why a positive corporate culture can accelerate the net zero transition.

The Report is based on Tina’s extensive market research, including interviews with over 65 senior executives and years of corporate governance research and practice, which overwhelmingly reveal a crisis in corporate culture and direct links with the financial bottom line.

Tina’s practical tools – the Corporate Supermap and the Five-Step Sequence for decision-making – can help companies develop and implement strategies to improve corporate culture that build resilience and ensure long-lasting financial performance.

Sarah: What is corporate culture, and why is it financially material to banks and other organisations?

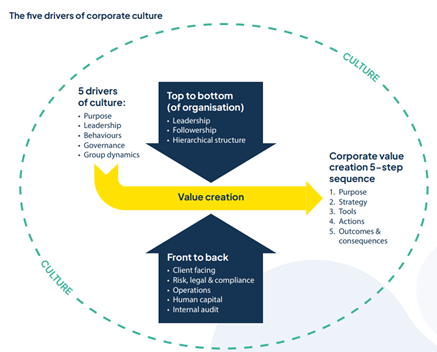

Tina: Corporate culture is the glue that holds an organisation together. It is the practical experience of how an organisation operates top-to-bottom (i.e. through leadership structures and hierarchies) and front-to-back (i.e. across an organisation’s divisions and functions) to deliver operating and financial outcomes.

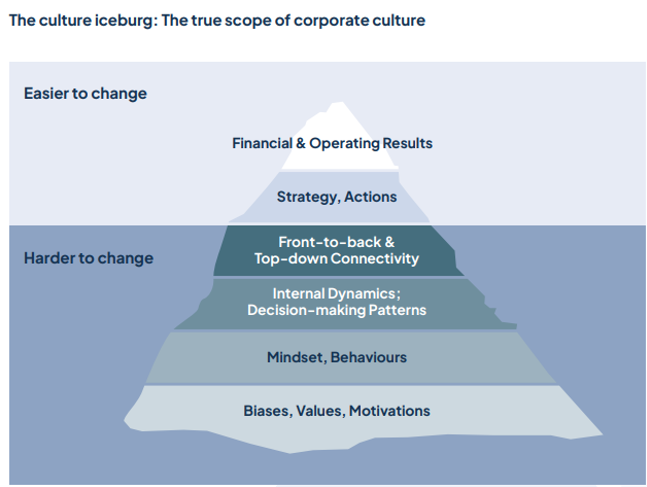

Definitions of culture that revolve just around values and ethics are only scratching the surface. Corporate culture has its source in values, but is not only values. Rather, corporate culture can be seen as the aftertaste of values on the ground.

Culture should not (only) sit within Human Resources (HR) departments. It is more than HR accountability; it is a risk accountability; it is a finance and operations accountability; and, depending on the organisation, it is a marketing and procurement accountability.

This is because corporate culture failures breed risk events (like Boeing as an extreme example), financial collapses (like Credit Suisse as an extreme example) and operational discontinuities that lose banks time, increase client dissatisfaction rates, and reduce internal congruency and alignment in strategy execution.

Interestingly, my research also reveals that corporate culture is not only the reason why banks are not performing, but also why the climate transition is not happening at the pace required. There is a disconnection between espoused values and genuine culture on the ground; espoused values mean nothing if not embodied in action.

To break this down further, I talk in the Report about the five drivers of culture: purpose, leadership, behaviours, governance, and group dynamics.

- Purpose: for profit-making organisations, purpose is what motivates an organisation to generate profit consistently through time by providing a service or product. (For non-profits, purpose is found in the organisation’s theory of change). When considering or communicating about an organisation’s purpose, it’s important not to ‘virtue signal’ or, in the climate context, greenwash or greenwish.

- Leadership: leadership means the people who drive purpose. Leadership must be inclusive, cannot be self-referential, and must focus on internal dynamics: i.e. how top-to-bottom and back-to-front processes point in the same direction to execute the bank’s strategy. I measure the success of leadership in the following it creates internally. We see the biggest cultural dislocations in leadership.

- Governance: governance describes the rules of engagement for an organisation; its modus operandi. However, organisations must be led by outcomes, not processes. Governance must aim to serve people as an asset, not an expense.

- Behaviours: behaviours are seen through the positive output they contribute to the bottom line, in the form of productivity, innovation, and conducive principles to executing the bank’s strategy. They are not out-of-context compliance statistics.

- Group dynamics: Finally, group dynamics are the direct consequence of leadership and governance across organisational structures and resources. Group dynamics are pervasive and deterministic.

The biggest problem with cultural (and therefore financial) underperformance is a lack of congruence between the five drivers. Take for instance banks with net zero climate commitments and 2030 interim targets (i.e. the purpose). Most banks have focused on introducing ESG board committees and sustainability executive centres of excellence (i.e governance). However, because they have not moved further to understand and re-price their risk and credit models, they have not incentivised the launch and scaling of novel and profitable climate products, and are not enabled to make more than five basis points on their sustainability-linked loans (i.e. poor leadership, governance, and internal dynamics). Because there are no granular divisional climate targets, there are no incentives to conduct genuine client engagement, or to generate green P&L related bonuses (behaviours). As a result, banking green asset ratios are abysmal (a median 1.7%) and sustainability divisions end up mainly serving reporting requirements, not generating profits.

Sarah: What are the Corporate Supermap and Five-Step Sequence? How can these tools, and the other recommendations in the Report, help boards shift their understanding of corporate culture from being a values- or ethics-based “soft skill”, to a determinative driver of financial performance and longevity?

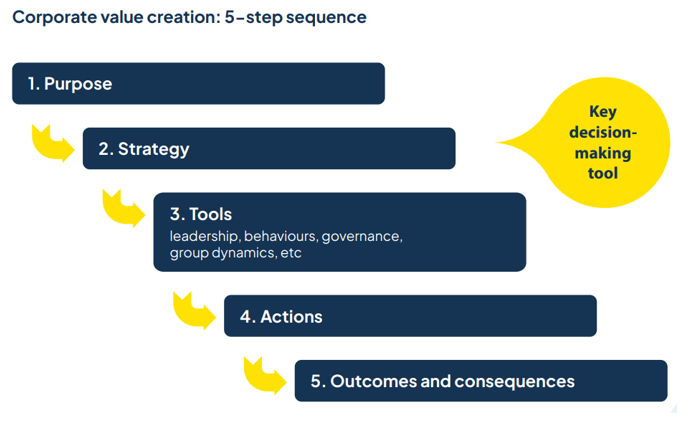

The Corporate Supermap and Five-Step Sequence are tools that bring back discipline and congruence across the five pillars of corporate culture and decision-making habits, respectively. Although the tools can be used separately, they are complementary and will provide the discipline to help decisionmakers convert strategy (in the Supermap) into action (through the Five-Step Sequence). The tools reveal an organisation’s priorities, where the quick wins sit, and how to build momentum to continue reaping gains in the future.

The Report also sets out clear recommendations for directors, finance, risk and compliance, finance and accountants, HR, regulators and more.

The Corporate Supermap

The Corporate Supermap helps directors and decisionmakers conduct deep analysis of how the people, processes, and finance elements of their organisation work together in practice, identifying key strengths, weaknesses, intersection points, and enablers. It brings together an organisation’s financial planning, people planning, systems planning, and strategic planning in a clear, comprehensive strategy that will deliver congruence across the five pillars of corporate culture – and in turn will help generate profit – over the short, medium and long term. Although organisations may have 2050 net zero targets, most strategic planning happens in short, maybe three-year, cycles. Organisations can use the Corporate Supermap to set credible 2030 transition targets.

Working through the Corporate Supermap process will highlight required areas of investment in leadership, workforce, behaviours, group dynamics and governance to better integrate the organisation’s front-to-back and top-to-bottom processes, deliver its strategy more successfully, and achieve its commercial purpose.

Once organisations create their Supermap – whether it is for the purposes of climate transition or any other strategic transformation – they should move into the Five-Step Sequence for decision-making to implement it.

The Five-Step Sequence

The Five-Step Sequence is a framework that integrates the five culture drivers into corporate decision-making, and helps organisations foresee strategy into outcomes before they pull the trigger and end up with unfortunate strategic U-turns, which are all too frequent.

Currently, when taking decisions, most directors and decisionmakers do not get past ‘purpose’ and ‘leadership’. This is because it is easy to talk, and real change requires discipline.

Decision-makers must work through all five steps to ensure changes are comprehensive, well thought out, and well planned.

Execution itself drives strategy, as Michael Porter had famously said.

Sarah: The Report highlights many areas of corporate culture that are widely misunderstood and mismanaged. Why did you choose to focus on climate change to highlight your findings and demonstrate the business case for corporate culture?

Tina: The Allianz Risk Barometer 2024 Report found that 6/10 top business risks in 2024 related to climate change. It fascinates me that we have all recognised climate change as a systemic, material financial risk to the economy, but we have not moved past this.

I chose to focus on the climate crisis in the context of banks because a lot of internal risk management initiatives within banks are still nascent, nominal instead of dynamic, and scratching the surface, because they haven’t gone into probability of default, which changes the credit outlook of a transaction. This goes completely against the nature and extent of climate related risks.

Sarah: The Report focuses on the financial sector. Are the findings applicable to all organisations?

Tina: Absolutely. I focussed my research on banks because they are regulated, meaning there is a lot of data on corporate culture and financial performance (but also because I was a banker!). However, the Report’s findings are applicable to all organisations. For instance, I’ve already seen a lot of interest in this work from private equity houses.

Sarah: What is the role of the Board in building a healthy corporate culture?

Tina: The role of the Board of directors is absolutely primary in building a healthy corporate culture. The Board sets the tone. It looks to the future by setting the organisation’s purpose and strategic direction. It looks to the past by monitoring how directors and executive management deliver on the organisation’s purpose. The Board anchors the organisation’s leadership, dynamics and behaviours by establishing what is desirable and what is unacceptable. It sets the boundaries on internal dynamics and governance. The Board is ultimately accountable for the consequences of a bad culture and its financial aftermath.

In practice, this means, for example, that the Board should procure and supervise the creation of the organisation’s Corporate Supermap. Together with executive management, it should arrive at the top 3 priorities of intervention and monitor their execution front to bank and top to bottom. By monitoring cashflow, profit margin impact, and operational integrity, the Board will help the organisation be more resilient and financially sustainable. If it fails to do so, you see laxness and attrition across the organisation and faltering in terms of financial progress.

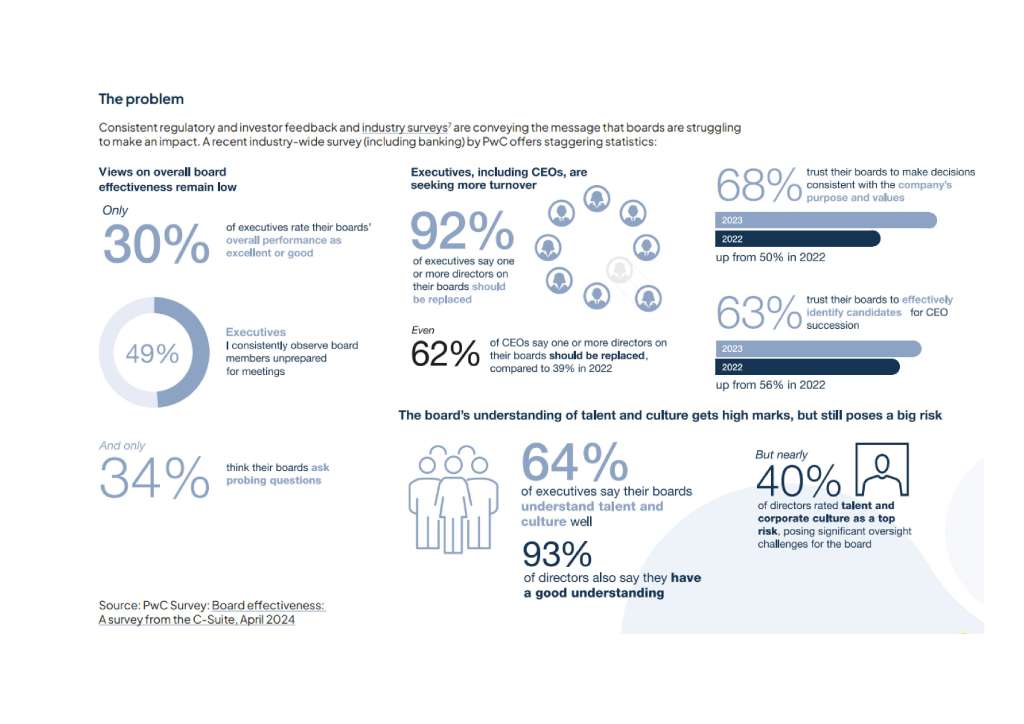

However, Boards are consistently underperforming, with only 30% of executives rate their Board’s overall performance as excellent or good. Research reveals that many Boards of banks are removed and disconnected from corporate culture, with only 36% of executives reporting that their Boards understand talent and culture well. Boards are not asking enough probing questions, are not coming prepared for meetings, and are not trusted to identify the right CEO candidates. 62% of CEOs say that one or more current directors should be replaced. Directors don’t quite understand a bank’s culture and don’t follow through on the necessary culture-related decisions. Indicatively, some interviewees in the Report noted that “boards are usually the last to know what’s happening at the bank” and “boards don’t walk the floor to get the pulse of the bank.” These speak to significant gaps in leadership, dynamics and governance that undermine the Board’s main role.

If Boards are generally underperforming, it is unlikely that they can rise to meet complex, transformational challenges like climate change, making it harder to strategise and guide and supervise the production and implementation of a credible climate transition plan.

Sarah: What steps can the Board and individual directors take to better educate themselves and understand corporate culture, particularly in relation to challenges like the climate crisis?

Tina: Step 1 is introspection and formal accreditation. Start by asking the Board simple questions: what is governance? What is strategy? What is culture? It is likely that every director will give different answers. In fact, many directors still do not recognise that strategy is a Board mandate, or that directors owe their duty of care to the company and not shareholders. Until directors are properly trained to understand these basic elements of their roles and accountabilities, Boards will likely remain ineffective in addressing transformational issues like culture or climate change.

Step 2 is asking probing questions and internally analysing the Board’s effectiveness. Ask why performance and trust are so low? Consider what specific and targeted measures the Board can make to address specific challenges. Regulators should consider accrediting board evaluators, to ensure that evaluation feedback is accurate, granular, and taken seriously.

Step 3 is Board education. Many directors do not have a full understanding of their role on the Board, and this needs to change. Prior executive or accounting experience does not necessarily make an effective director. We need to go back to basics and provide training to Boards setting out what is expected of them. Boards need to understand the levers at their disposal to improve culture and raise performance. Targets, annual aspirations, probing questions… these are all important tools.

Step 4 is putting lessons and strategy into action. Boards must:

- Behave as a team, create a conscious performance culture, maximise impact, and strengthen the bank’s overall culture;

- Rely on decision-ready leadership and mindset dashboards to enhance leadership effectiveness, address internal dynamics and behaviours, and counter the overconfidence bias;

- Replace culture, ethics, and governance committees with an operations committee that is accountable for the Corporate Supermap; and

- Stay current through formal accreditations.

Sarah: In several places, the Report highlights the role of corporate climate transition plans. What guidance do you have for companies and boards currently creating transition plans?

Tina: Where necessary, climate transition plans should be granular, short-term and decision ready plans that are rooted in an organisation’s detailed and quantitative financial materiality assessment. The quality, rigor and depth of an organisation’s climate materiality assessment is a strong indicator of how it has integrated sustainability into its strategy, internal dynamics, and leadership.

But not every company needs a detailed climate transition plan. In fact, short form transition plans – or even no transition plan – may be appropriate for certain companies, in certain conditions.

Further, the UK Transition Plan Taskforce, and transition plans in general, should not be used as a reporting framework. A transition plan is a framework that should come into play only after organisations have a good understanding of timing (long, short and medium term) and have conducted a materiality assessment (and how to do this top-down and front-to-back). Transition plans should be investor and decision-ready business strategy documents, not long, detailed reports. It’s all a question of intentionality in addition to materiality.

The Corporate Supermap can be the basis of a climate transition plan – and indeed any climate reporting, for example, under the CSRD. The Supermap brings CSRD together in a way that does not make it a painful reporting exercise. It’s a strategic business plan, with risks and opportunities and pricing woven in.

Sarah: The Report highlights the importance of trust as a “core measure of cultural performance”. This refers to trust between management and employees as well as trust with external stakeholders (e.g. clients, customers, investors). How can directors build trust, particularly around critical, emotive and divisive issues like the climate crisis?

Tina: Big organisations are complex, and change takes time. To build trust, directors should start to analyse, quantify and remediate the bank’s top 3 “say-do” gaps. Directors can use the tools in the Report to do this. This could be around climate change. The Corporate Supermap will help to identify material say-do gaps in your organisation, and the Five-Step Sequence will help you make decisions and implement new processes that will fill the gap, focussed on people, processes, outcomes, and financial reporting and monitoring.

Sarah: Most organisations currently take a risk-based approach to the climate crisis. However, the Report highlights the limitations of this approach, which distances risk from business and key decision-making. How can directors move away from this mindset to create business opportunities from risks like the climate crisis?

Tina: Directors should focus on opportunities, as well as risks in an equal weighting, in fact put them in the same equation. Risk and opportunity are two sides of the same coin. Talking about risk without reward is an empty conversation, a half-filled sentence. Strategic decisions should be taken on a risk-reward basis, otherwise, they lack context.

Organisations are vulnerable to risks from the external environment (including climate risks) as well as adverse internal behaviours and dynamics (including how organisations respond to climate risks). If the fundamental appreciation of risk and compliance as core asset preservation and fraud prevention tools are lacking at an organisation, and are instead treated in a rigid and legalise sterile fashion, climate risks are bound to fall through the cracks (and already have on many occasions). By contrast, a granular and credible transition plan with top down and front to back connectivity and congruence demonstrates in practical terms how risk mitigation can lead to business opportunity. Organisations can use the Corporate Supermap and implement its findings with the Five-Step Sequence to help realise those opportunities.